COVID-19 shook, rattled and rolled the global economy in 2020

- By Agencies -

- Dec 31, 2020

When 2020 dawned, the global economy had just notched its 10th straight year of uninterrupted growth, a streak most economists and government finance officials expected to persist for years ahead in a 21st Century version of the “Roaring ‘20s.”

But within two months, a mysterious new virus first detected in China in December 2019 – the novel coronavirus – was spreading rapidly worldwide, shattering those expectations and triggering the steepest global recession in generations. The International Monetary Fund estimates the global economy to have shrunk by 4.4% this year compared with a contraction of just 0.1% in 2009, when the world last faced a financial crisis.

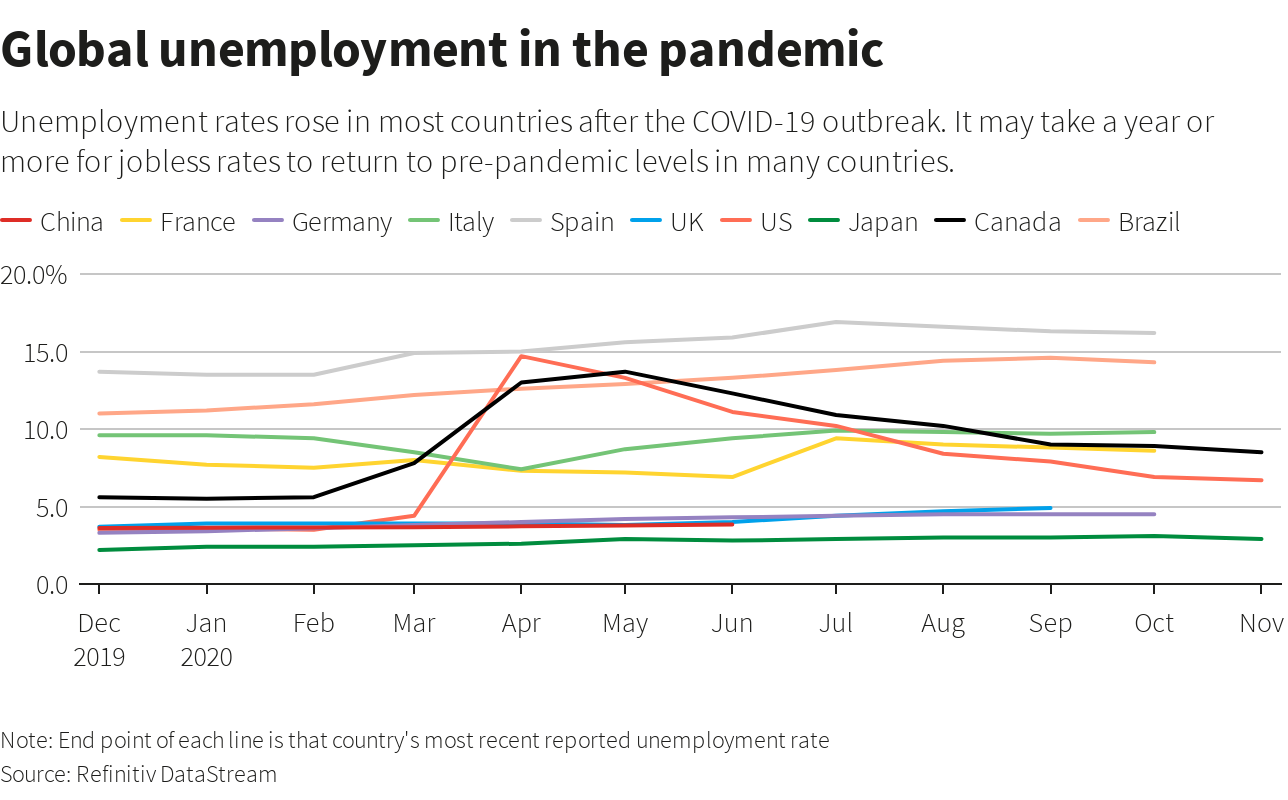

Government-mandated shutdowns of businesses and any non-essential activities in much of the world unleashed a wave of joblessness not seen since the Great Depression. Still, unemployment levels varied dramatically across the globe.

In some countries, like China, COVID-19 infection levels were effectively suppressed through strict but relatively brief lockdowns, allowing unemployment rates to remain low. Others, such as Germany, deployed government-backed schemes to keep workers on company payrolls even as work dried up.

Elsewhere, including in Brazil and the United States, the uncontrolled spread of the virus and patch-work government health and economic responses fueled rampant job losses. Some 22 million people in the United States were thrown out of work in March and April alone and the unemployment rate jumped to near 15%.

Most economists expect it to take a year or more for labor markets to return to something resembling the pre-pandemic era.

The pandemic delivered a body blow to global trade, with export volumes dropping abruptly to their lowest in nearly a decade in March and April.

The recovery since then has been led largely by China, which stands alone among major economies in seeing year-over-year growth in exports.

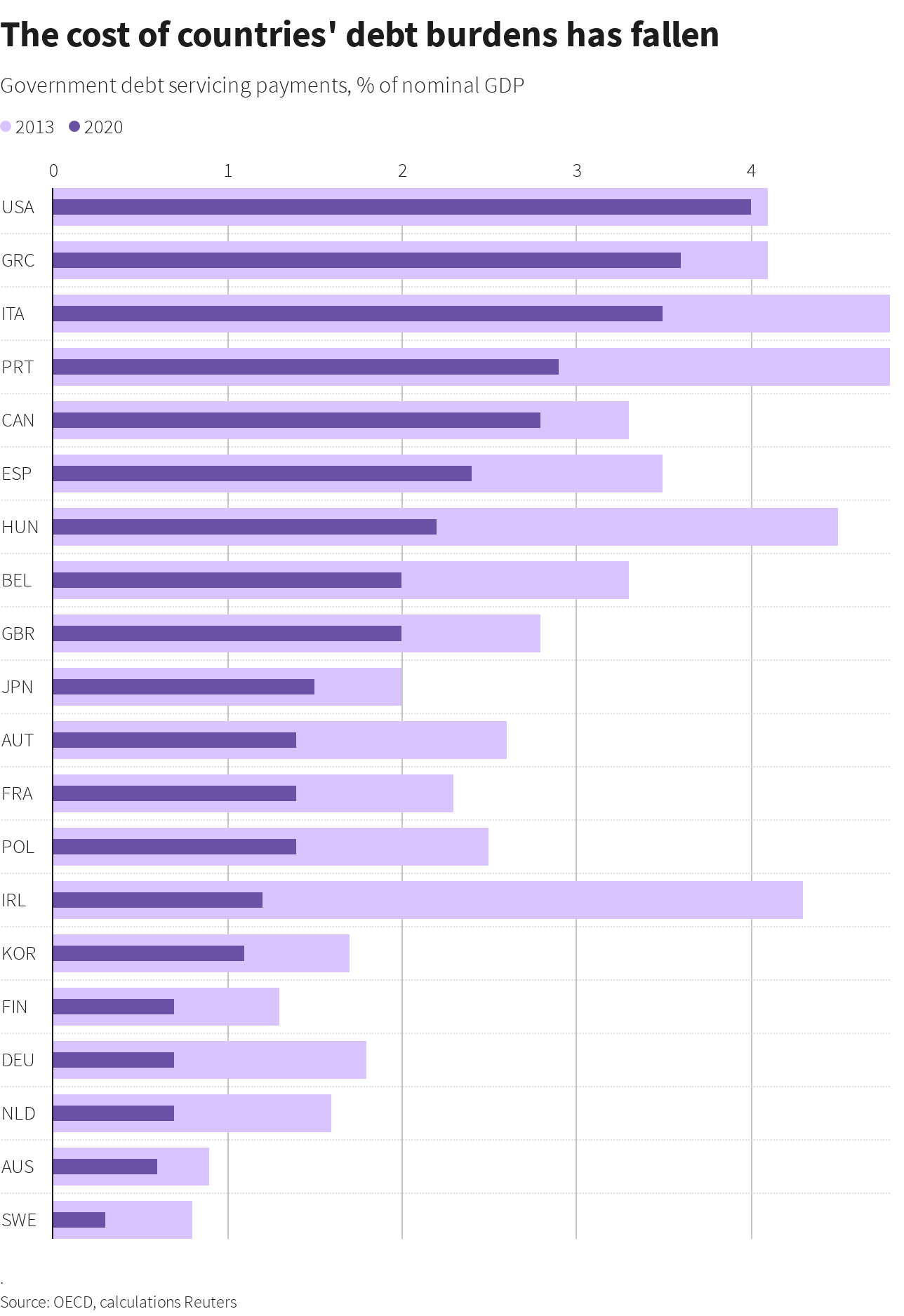

Unprecedented levels of government stimulus prevented even larger damage to many economies but also added to a global mountain of sovereign debt amassed by governments, raising questions about whether a financial crunch is the next crisis the world must deal with.

However, historically low interest rates hovering around – and sometimes below – zero percent mean that debt servicing costs for the Group of Seven (G7) economies are at their lowest since the 1970s, when the debt burden was only a fraction of what it is now.

“Debt today is sustainable and it will remain so for a few years because as long as economic activity and employment have not recovered momentum, central banks are unlikely to do anything with their interest rates. That allows governments to keep up the fiscal support in the form of retention schemes and support to firms,” said Laurence Boone, the OECD’s chief economist.

One offshoot of that largesse has been that consumer spending has held up better than many had expected. While spending on services plunged and remains depressed – at restaurants and for travel and leisure in particular – consumers did lay out for goods, especially big-ticket items such as cars and home improvements that benefited from rock-bottom interest rates.

As a result, retail sales in many economies are up on a year-over-year basis, in some instances by more than they were at the end of 2019.

Another direct effect of all that government spending has been a surge in savings among consumers in many parts of the world. Government support payouts in developed economies padded household bank accounts and, with consumers hunkered down in the pandemic’s early days in particular, savings rates soared.

They began returning to earth in the latter part of 2020 but remain well above pre-pandemic levels. Some economists see this as the dry tinder to help fuel an economic rebound in 2021 and beyond when COVID-19 vaccines allow a wider recovery to take hold and consumers to begin moving about – and spending – more freely.