Mughal Monetary World

- By Zoya Ansari -

- Jan 04, 2023

The best thing about the Mughal Empire was that it conducted most of its affairs on paper and this paper trail did survive in quite a large measure facilitating taking account of the Mughal rule.

Mughals were very liquid in the financial sense and could fund any enterprise its elite proposed to undertake.

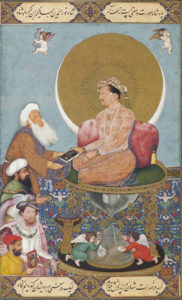

Mughal revenue windfall was the highest among contemporary Ottoman and Safavid empires letting the Mughal rulers take advantage of the best talent available both on the battlefield and in governance matters. Mughal imperial coinage was of an unprecedented quantity and quality and was highly valued and commanded a strong purchasing power.

The Mughal silver rupee was the most popular currency having been standardized at about eleven grams. The most crucial factor of Mughal coinage was that it successfully maintained its standards from the reign of Akbar in the mid-sixteenth century until the break-up of the empire in the first half of the eighteenth century.

Mughal rule was widespread in the subcontinent guaranteeing that its currency circulated freely and uniformly from Kabul to Dacca and from Surat to Madras. Imperial mints located throughout the empire struck coins to the same standard. As the empire expanded so also did the area of circulation for the rupee and its copper and gold counterparts. Mughal currency easily and quickly superseded virtually all preceding currencies and local and regional coinages.

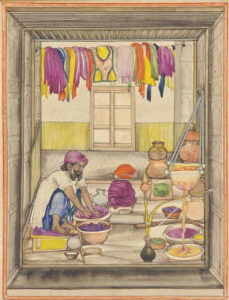

The Mughal administration followed the system of free minting, open to all who wished to have coin struck from non-official coin or bullion. The system of discounting older coins in favor of the coin dated in the current regnal year was also in vogue. Mughal numismatic presence is extensively recorded and is well-known to have been in wide circulation and enjoyed high levels of acceptability.

Though most of Mughal rule was well-documented through the monetary transformation brought about by Mughal monetary practices are now appropriately analyzed, however, like the state which created it, the Mughal monetary system was powerful, flexible, pervasive, and longer-lasting.

The measure of success could be gauged by the fact that Mughal currency was circulated in extremely large numbers both in private and public fields of activity. It is duly recorded that the number of Mughal copper coins and silver rupees minted and released was very large as imperial mints turned out silver rupees in numbers sufficient for expanding trade and commerce, the meeting tax demands, as well as for royal and noble hoarding in treasuries, and for conspicuous consumption. It is estimated that the number of silver rupees in existence must have run into tens of millions. Interestingly this enormous mint output occurred in a region lacking any significant output of silver and gold and with only limited copper production.

The Mughal currency relied upon stocks of treasure released after the conquest as happened in cases of the annexation of Malwa to the conquests of Bijapur and Golconda with the royal treasuries of regional kings yielded stocks of coin and bullion to the imperial mints. Moreover, Mughal money-handlers also relied upon imports both from east and west, over both land and maritime routes.

The export of textiles and spices among other products, aided by the skills and capital of Indian traders and ship-owners, and caravan operators, ensured a favorable commodity balance of trade. The supply of precious metals was provided a fillip by the vast streams of New World silver and gold that began to arrive in the Mughal Empire. By the end of Akbar’s rule in 1605, these flows were enhanced by direct India to Europe traffic of textiles and spices exchanged largely for precious metals by the East India Company and this mutual advantage was gained both by western companies and the Mughal Empire.

It was widely known that one could carry all sorts of silver into the Empire that could also be conveniently converted into currency by many mints situated in the length and breadth of the Mughal Empire. It was mentioned that the universal medium of tax collection for the Mughal treasuries was an imperial coin and the foreign coin was not acceptable, therefore, it was in the interest of the moneychangers and bankers to initiate the conversion of foreign currency at the mints. This practice implied that the policies of the Mughal state were designed to ensure that the imperial mints absorbed the inflow of silver and gold and placed this in circulation as silver and gold coins of standard issue.

Though most of the Mughal currency circulated within the borders of the empire but limited quantities did travel within the wider Indian Ocean region also. However, the Mughal rupee did not serve as a major trading currency beyond the subcontinent. Imported silver and gold augmented the coinage stocks of Mughal India.

It was noticed that decade after decade the Mughal state put more and more coins into circulation in its territories and, though some losses were recorded due to wear and tear, this sustained level of mint production and its cumulative effect on imperial monetary stocks. It was also noted that the growing stocks of coins did not long remain sterile in hoards as the institutions and practices of the empire favored the exchange of coins rather than commodities.

The expanding imperial land tax system acted as a constant stimulus to market activity and the result was that state requisition of a large share of production increased the demand for money. The Mughal financial managers encouraged all parties, from the producing peasant to the highest grandee, to support and facilitate the conversion of agricultural produce into money. Proceeds from sales of produce and official and unofficial loans and salary payments moved money from the city to the countryside. It is imperative to realize that the Mughal Empire paid its officials and military in cash which increased the requirement of minting more currency.

During the Mughal times, the predominant aspects of economic activity ensured patterns of commodity production, internal trade, and export outlets that encouraged money supply and further liquefied the Mughal treasury. Mughal Empire economy upsurge and the need for trade and banking witnessed the refinement of ancillary monetary instruments. Monetary transfers at a distance became easier and less costly with the proliferation of reliable private mechanisms such as hundi and hawala and so also did short-term commercial credit. Hundis were also utilized by imperial fiscal officials frequently for the transfer of funds. The royal family and members of the ruling nobility used this method for remittances and kept money circulation flowing.

The expanding state and the burgeoning market relied upon a growing and flexible imperial monetary system devised by the Mughal rule underpinned by huge and growing stocks of coins provided the means for a growing emphasis on the market exchange on a cash basis. One result of this seems to have been a deepening level of monetization within the empire.

The land tax demand in the expanding borders of the empire coupled with commodity sales in an intensifying network of markets increased the number and velocity of coins in circulation. The adroitness of the Mughal financial managers ensured that the coffers of the state remained full enabling it to provide basic requirements of life to its citizens through a strong economy, stable currency, and flexible regulatory mechanism.