Mughal patronage of manufacturing

- By Web Desk -

- Dec 11, 2021

The Mughal Empire provided a consistent public good in shape of peaceful living environment having law and order in the length and breadth of its domains.

The law and order ensured an important precondition for the growth of manufacturing. It is widely acknowledged that during the Mughal rule, the prevalence of law and order and absence of regional trade barriers led to the integration of markets.

The Mughal rule is also described as the time when the process of growth of urbanisation led to growth in towns and cities that were mostly inhabited by the elites and nobles famously known to prefer high standards of living and were known for conspicuous consumption. It was obvious therefore that these developments had significant impact on Indian manufacturing that became a significant feature of the Mughal Empire.

Mughal rule witnessed tremendous increase in the extent of monetisation of the economy that reduced the magnitude of customary mode of exchange based on the old system and effectively intensified the market-mediated exchange relationship. This development also assisted the creation of a new class of traders and merchants and this creation was an important condition for the birth of a fresh and flexible manufacturing throughout the Empire. It is pertinent to mention that before the Mughal Empire crafts were still an integral part of agriculture and were not distinct from the rural economy. The negative feature about this field was that it was associated with social division of labour based on caste lines was extended to include artisans also.

The manufacturing-friendly Mughal economic policies resulted in the decline of the old system due to monetisation of the village economy that was created by collection of land revenue in cash. Subsequently, the old system also lost grip on social order because of migration of several artisans to emerging urban areas to pursue their vocations.

The Mughal rule succeeded in introducing a manufacturing pattern according to which the entire production of manufactured items meant for long-distance and medium-distance trade was carried out by artisans who were fully weaned away from the traditional system. This meant that the Mughal system increased the mobility of artisans, which increased the availability of artisans to participate in traditional flexible manufacturing.

The size of the market increased due to integration of several fragmented markets into a single political unit and by eliminating trade barriers.

The dynamism of the Mughal system was the byproduct of effective patronising and monitoring of various aspects of life lived in its domains and it was ensured by its efficient state machinery. The cardinal economic principle governing the administration of the sprawling Mughal Empire was based on extraction of surplus from agriculture to maintain the vast army of the empire and to achieve this goal it required the economic activity of the empire to widen. The Mughal mansabdari system was dedicated to this goal and was ably assisted by a skilled lower middle-level bureaucracy consisting of trained persons in bookkeeping auditing, correspondence, procurement and supply, record keeping and maintenance of stores. In addition this politico-military administration created a vibrant and ambitious aristocracy and nobility that crucially generated demand for manufactured goods and helped in tremendous increase in this important economic field.

One crucial factor helping the economic development and its attendant field of manufacturing was the development a network of roads, including the major road that is now popularly known as Grand Trunk Road along with roads that connected Punjab to the town of Sonargaon, near the Bay of Bengal, Agra to Burhanpur, Agra to Jodhpur and Chittor and Agra to Lahore. These roads were further extended to Cambay, Surat, Ahmedabad and Multan and intensified the connectivity between different markets and facilitated the movement of goods across different parts of the empire.

The development of infrastructure coupled with monetisation of the economy and expanding size of the market led to extensive trading, and created premises for the formation of a class of merchants, traders and moneylenders. The result was that each region gave birth to certain trading communities, which subsequently developed a network of artisan’s workshops to evolve traditional flexible manufacturing and later on became entrepreneurs when the process of modern manufacturing began.

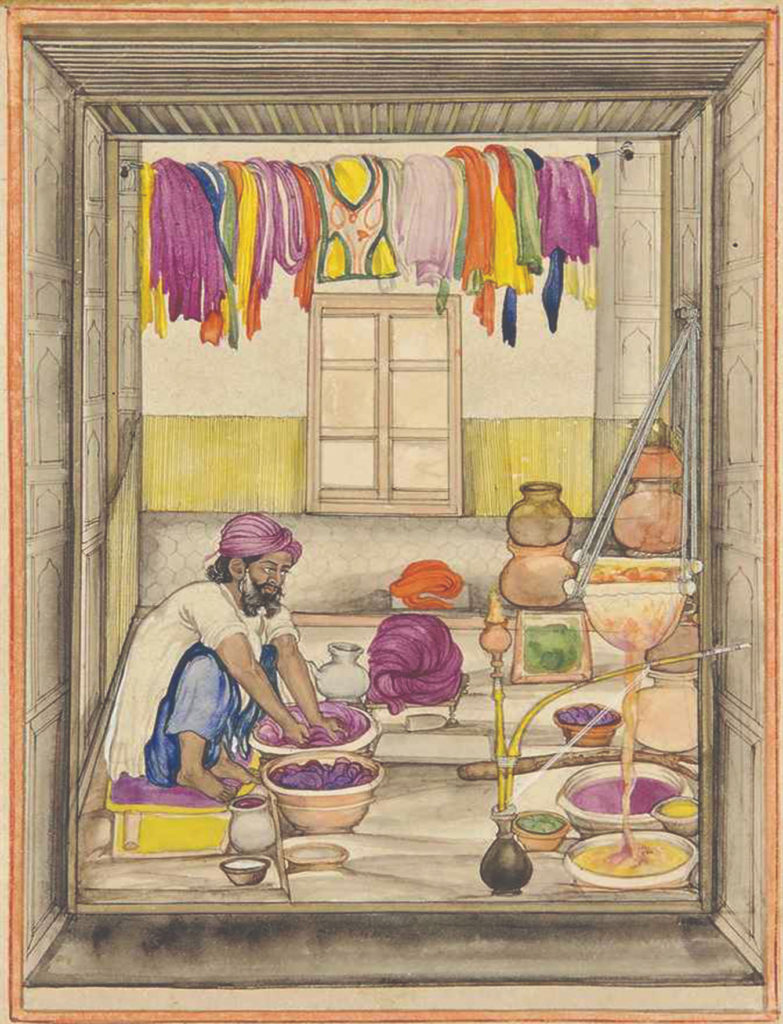

It is widely acknowledged that the Mughal Empire made it possible for the subcontinent to emerge as an important manufacturer of some agro and metal-based products. In this context the most important industry experiencing high growth rates was the textile industry and Indian cotton and silk textiles were traded along most of the port cities located in the Indian Ocean, Arabian Sea and Red Sea and also through caravan routes to Central Asia.

One crucial boost received by manufacturing in the Mughal Empire was from its ruling class maintaining an extravagant lifestyle and their need for luxurious goods was satisfied by artisans manufacturing luxury handicrafts like high-quality cotton known as Dacca muslin, jewellery including gold as well as silver, cutlery, decorative swords and weapons. In addition the fact that the Mughal nobles maintained households with large numbers of wives, concubines, slaves and domestic servants and the entire consumption practices of this affluent class created urban culture and the pattern of their demand manifested into an occupational pattern, where a large proportion of the working population was engaged in the manufacturing of handicrafts and providing services to the elite.

Mughals mostly concentrated on urban centres and encouraged non-village economy and the records portray that the income generated by it was more than the village economy.

It was recorded that although the village economy gave employment to 72 per cent of the total working population and contributed 45 per cent of the national income but the non-village economy provided employment to 18 per cent of the population, while contributing 52 per cent of the national income. Essentially, non-village economy of the Mughal empire consisted of wide segments of the people including the Mughal emperor, court, mansabdars, jagirdars, native princes, hereditary zamindars, merchants, bankers, shopkeepers, traditional professionals, soldiers, urban artisans, construction workers and domestic helpers.

These manufacturing and trading communities were involved in commodity trading, usually financing the working capital needs of artisans. Some of the big traders and moneylenders formed big banking firms that were engaged in transfer of large volumes of money from one place to another, and through a wide variety of financial instruments and transactions. These developments proved the burgeoning of vast monetisation of the Mughal economy and system of credit in Mughal India made it essential to evolve alliance with large trading banking firms.

The Mughal state depended on them for procuring commodities, as well as cash and credit on a regular basis, because the main source of revenue, land revenue was essentially handicapped by vagaries of nature.

Mughal emphasis on manufacturing increased urbanisation and its is recorded that about 15 per cent of the total estimated population between 107 and 115 million lived in urban areas that was quite a large number by the standards of the age. The textile industries of Patna and Banaras reaped immense advantage from transporting their products through the River Ganges to the European trading centre at Hugli.

These networks of cities and urban centres provided appropriate economic conditions for the growth of inland and overseas trade in manufactured goods.

The writer Zoya Ansari is a freelance contributor