Bengalis in Pakistan forsake culture, language for chance at citizenship

- By Hunain Ameen -

- Sep 08, 2022

KARACHI: They say any language is the road map of its culture for it tells you where its people come from and where they are going. What would it mean when a systematic erasure of a culture is being carried out? Could it be likened to breaking their cultural trajectory?

This may be true for a number of Bengali people who either chose to stay in Pakistan post-Dhaka fall, on December 16, 1971, or immigrated here later for economic reasons, for both meet the same fate here owing to callous prejudice by the state and local communities’ individuals, whose idea of patriotism requires of them to consider Bengali hate-worthy. “They are traitors,” a random passer-by would tell you that when asked of Bengalis in general.

For this social experiment, ARY News asked a bunch of people why Bengalis are discriminated against so much? Most of them plainly replied: they betrayed us. Second most common comment was that betrayal runs in their veins.

Instilled in the generations of other native communities via the spread of disinformation against not one person, one unit, one institution, one act, but simply against an entire ethnic community indiscriminately, this preposterous hostility by and large results in one thing: Bengalis hiding behind their heavily affected Urdu accents to fit in.

“Even when we go to clinics, or attend ceremonies, people shamelessly avoid us or insult us,” says Tasleema, a Bengali resident of Karachi’s Machar Colony, and a mother of two.

“I have nine children but none of them can read or write bangla.”

Wading across the mud- and sewage-encrusted streets of this neighborhood everyday, where houses are small and unplanned huts and shops are strewn across unpaved streets, hundreds of thousands of Bengali people, most of whom have been rendered stateless with ID-cards blocked, go to work on coast, factories, and markets for their wages. Most of their women work as house helps in adjacent areas, while some labor away in fishery of West Wharf, an area that is contiguous to Machar Colony. For each one of them, making a living means socially assimilating themselves into the local culture.

“People discourage their children when they speak or play with ours… ‘don’t play with Bengalis,’ they often say right before our eyes,” she said.

Tasleema is in her mid-twenties. She is still waiting for her national ID card so her kids can get B-Forms, essential, inter alia, for admissions in the school. She says that one thing is for sure now, Urdu language and local cultures are the only solution.

“What can we do when Bangla is so obviously hated here? Do we stop interacting with people and confine ourselves to just our close-knit communities? No, we learn local culture and adapt to their ways because we live in a society,” she added.

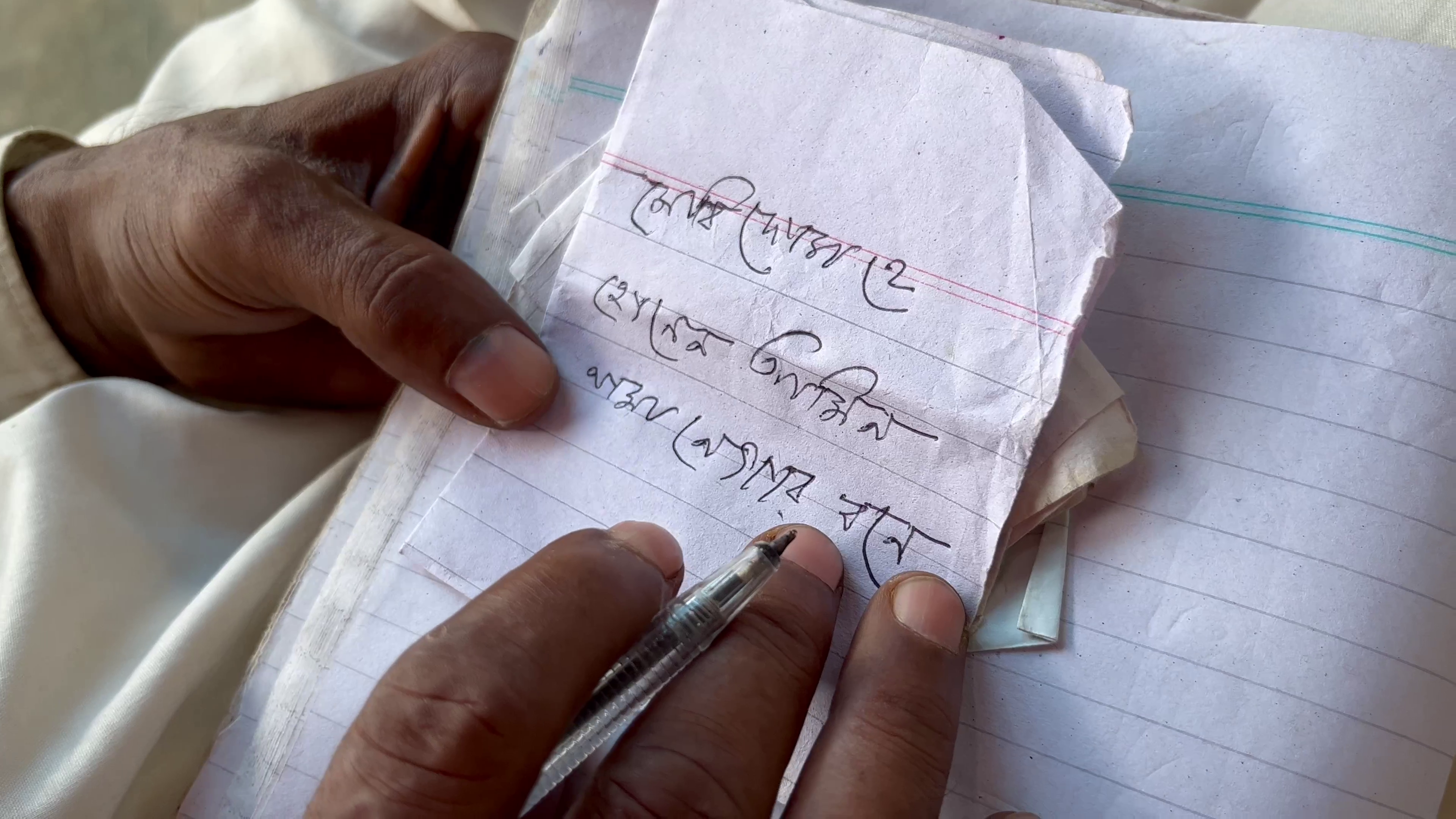

Jafar Ahmed understands this dilemma. He’s among the few Bengali people who can still write and read the Bangla script, a derivation of Brahmi style ancestral to many sub-continent languages. As he discussed the matter with ARY News, he wrote a sentence in Bangla that read ‘I am Jafar’, however, none of the Bengali people gathered around him could read what he wrote.

EXPLAINER: New Karachi local government to look like this

Some 90 per cent of the Bengali people in Pakistan don’t know how to read or write Bangla anymore, claimed Ahmed. This was substantiated by Meezan Farooq, an official of Nazrul Academy that houses Bangla book library, but is in shambles now.

“Nobody visits this library anymore,” Farooq said, “…if you are planning a visit, let me know in advance so I dust and clean books and tables.”

Tucked away far into the Pakistan Secretariat complex in Karachi’s Saddar, the Nazrul Academy’s whole job today is to gather dust and maintain its spree of days of no visits. Once a celebrated Bengali cultural center, the institution lost its glory after being displaced so many times that most people you ask about it would tell you it’s not here anymore.

“That academy was demolished under top court orders, it’s not here anymore,” one policeman said when asked for directions smack dab in the middle of the secretariat. Only, however, part of the statement is true.

“what’s the last time you heard a Bangla song or heard about a new Bangla book launch?”

Nazrul Academy, with around 3,000- to 4,000 works of Bengali literature, was indeed demolished, but it was housed somewhere down the winding lanes of Pakistan Secretariat where hardly anyone knows where it is.

When you burn somebody’s house, whom would they rescue, books or family? Haya Fatima Iqbal asks rhetorically, explaining that the common Bengali folk are reduced to living day to day with their identities snatched by the state. “Their tragedy is very much real, they have to secure food daily for their family and most of them just subsist.”

The award-winning documentary filmmaker and an assistant professor of the subject at Habib University, Iqbal said as rich a culture as Bengali’s is, and as vast a cosmopolitan as Karachi, you would expect volumes of new literature and variety of new music emerging from them, but what’s the last time you heard a Bangla song or heard about a new Bangla book launch?

Karachi Garbage Story: Ragpicker children at mercy of… everyone

Eradicating their statehood, the state is creating a system where it doesn’t matter anymore whether these people get paid, get paid less, wronged, harassed, or pigeonholed in the lowest job frames of economic hierarchy.

“The race of a common Bengali is to subsist and evade prejudice by concealing his Bengali identity. What business he has with literature?”

Advocate Tahera Hasan, who runs a welfare NGO for Bengali families seeking to reinstate their ID cards, told ARY News how the people who can read or write Bangla are rarely to be found, despite their near three million population.

Having fought a number of cases for Bengali people’s identity, Hasan explains that when you have to elude bored policemen stopping you for bribes, knowing your ID card would have been repealed, or when you cannot send your children to schools, or cannot get a job, and all of this is because you belong to a certain community and speak a certain language, you stop priding in that language.

TW: Acid attack survivor still dodges insults as her daughter dribbles football

Jafar learned reading and writing Bangla when he was still a kid and it was before the Bangladesh partition on December 16, 1971. His father chose to stay in Pakistan, but his uncle who taught him Bangla, among other family, left for the newly carved Bangladesh. While Jafar got his ID card made twice, first in the old manual system and later digital one, he couldn’t the latter renewed because of some ‘discrepancy’ that has not resolved in the past four years.

Jafar’s daughter is a competent gymnast who has bagged few local trophies but to vie in a bigger competition, or even to appear in matriculation exams, she would require a B-form, a proof of her citizenship, but that she can only get through her parent’s ID cards. For many young Bengalis like her, the choice of forsaking their cultural identity and heritage so they can get an ID card by state, is becoming discomfortingly simple.

When ARY News asked a National Database & Registration Authority (NADRA) official, he first refused to comment on record but then on the condition of anonymity shared that the front-line worker at NADRA can decide their fate whimsically.

“If he approves of the card renewal first hand, they can have their cards without any misery,” he said, adding, however that if the staffer chooses to mark a discrepancy, a Bengali or Afghani citizen can face a languishing age of trying to prove them as legitimate citizens. “The bribe culture is very much prevalent, too,” he admitted.

With this lethargic and discriminatory process forever looming large, Bengali culture is suffering at its worst. So much so that people of other communities mock them for the menial jobs they have been reduced to, while the term Bengali is thrown around as a slur.

Forever evading policemen due to repealed ID cards and struggling for survival, it seems the Pakistani Bengalis can afford little regard for Bangla culture.

Subscribe ARY Stories YouTube channel for more multimedia reports, documentaries & explainers