CHICAGO: Boeing is doubling down on its landmark new strategy designed to muscle in on the business of maintenance providers by making its next jet the laboratory for in-house services that could radically alter the global business model for selling planes.

Unlike Boeing’s last all-new design, the 787 Dreamliner, its proposed new mid-market plane will not bring a flood of revolutionary technical designs to the drawing board.

But it will give the world’s largest plane maker a chance to test its new business approach of designing the plane so that it generates lucrative services revenues for Boeing while also offering efficiencies to airlines over the aircraft’s decades-long lifespan.

Along with production costs, the new approach could help Boeing decide whether to invest the $15 billion or more in development needed to build the jet.

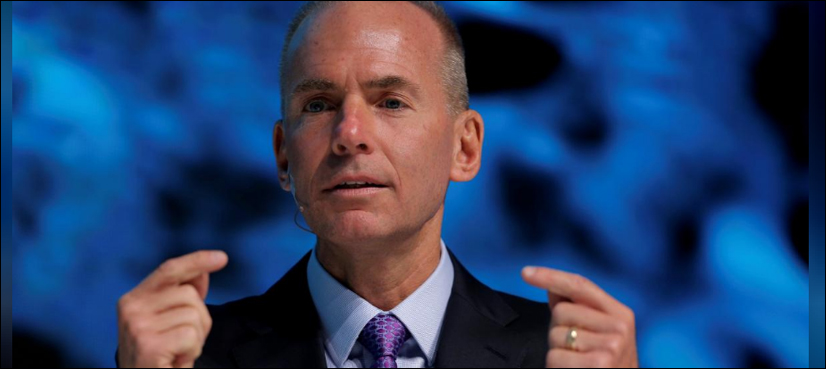

“If we decide to launch, it’s a big investment and it’s an investment that has to contemplate not only the product itself but all of our other strategic objectives,” Chairman and Chief Executive Dennis Muilenburg told Reuters.

“So you can imagine we would want to look at this airplane through the lens of lifecycle value as we are growing our services business,” he said.

Until recently, Boeing and Europe’s Airbus sold planes with little involvement in the way they were operated and maintained. Instead, that was work carried out by their own suppliers or third-party shops.

Heavy outsourcing on jets like the 787 expanded the trend by leaving suppliers – such as Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, which supplies the 787’s carbon wings – in command of key components.

While Boeing and others squeezed their balance sheets to launch jets, many of their suppliers used their design influence to forge profitable relationships directly with airlines as they conducted part swaps or repairs required by regulators.

“That seems a little out of balance, doesn’t it?” said Muilenburg, describing how the pendulum is now swinging back to give Boeing more control over parts and therefore the stream of aftermarket services that comes with owning a part’s design.

Read More: Boeing to build future Air Force One planes after Trump deal

“We do take the majority of the risk in developing new products, and we think that would cause us to want to gain the financial benefit of that risk-taking for the long term,” he said.

The long-term approach to the new jet is the latest evidence of changes in the $180 billion aero-aftermarket as planemakers jostle with suppliers – and even airlines – for control of repairs, training and data in pursuit of higher margins.

Last year, Boeing centralized services formerly spread across the company in a new division with a goal to more than treble sales to $50 billion in a decade.

The new unit posted operating margins of 15.4 percent last year, compared with 16.1 percent that United Technologies Aerospace Systems, a major supplier, earned from selling new equipment, services and aftermarket parts.

ENGINEERING DEPTH

The aftermarket is not entirely new to Boeing, and is common in defense, where Muilenburg ran services between 2008 and 2009. Airbus set ambitious internal targets last week and Canada’s Bombardier Inc (BBDb.TO) is banking on maintenance.

But after airplane demand peaked since 2014, Boeing has turned more aggressively to parts and services to help meet a target of doubling margins to the mid-teens by 2020. Its core jet margin widened to 9.6 percent last year from 3.4 percent in 2016.

To support the strategy, Boeing is bringing back key in-house technology like avionics – the brains of a modern jet -partly with an eye to future aftermarket revenue.

“It is important that we build out vertical capabilities that sustain our engineering depth…as airplanes become more digital,” Muilenburg said, adding that broader growth in the industry would also provide a boon to suppliers.

Suppliers say Boeing is also less willing than before to share risks – and profits – with them on the systems they do build. Instead it wants them to build to Boeing’s designs rather than leaving them with keys to the all-important aftermarket.

Already, there are signs the mid-market jet could see a swing away from risk-sharing towards straight procurement deals,the head of a major supplier told Reuters.

“It depends on the area of the airplane we are talking about but we are very clear in our intent to grow our services business, and part of that is bringing back inside some engineering and intellectual property,” Muilenburg commented.

The downside of doing more by itself, suppliers and analysts say, is that Boeing could weaken access to outside innovation, import risk and tie up capital and finite engineering resources.

Depending on how far this goes, industry sources say it may also herald gradual changes in patterns of cash generation.

While planemakers get paid on delivery, engine makers charge little upfront and make money on services provided over years.

Some analysts say new plane manufacturer strategies suggest those business models could start to converge and put pressure on them to be more generous with discounts on jets.

Muilenburg declined to address pricing directly, but acknowledged Boeing’s cradle-to-grave services strategy could have some impact on the timing of future income.

“The services business tends to be accretive to margin, but this does give us the flexibility of where we drive margin in the business with the idea of raising the bar overall,” he said when asked if bundling services could lead to bigger jet discounts.

Leave a Comment