Mughals enter India

- By Zoya Ansari -

- Sep 06, 2023

The Mughal advent in the subcontinent was a historical aberration that was not taken seriously in the beginning but slowly it came to grips with the geographical, ethnic and diversity of the vast subcontinent.

The massive and populous South Asian subcontinent contained various regions, each with its own ecology and complex sociocultural, economic and political conditions and histories. Never had all the distinct regions of the subcontinent been united under a single language, religion, economy, or ruler.

However, with local variations, most of South Asia shared some overarching environmental factors, like extreme rainy and dry seasons and also cultural features, notably some of the beliefs and social order of Hinduism. Though the country had Hindi majority yet there was a fairly noticeable sprinkling of Muslims who also ruled as a minority since a long duration spanning 320 years. The fact however was also evident and that both communities had very little interaction and the gulf had increased over time.

The subcontinent had distinct physical environments that defined each region. Perennial seasonally swollen rivers, mountain ranges and other geological features created four macro-regions: the Ganges-Jumna River basin of Hindustan and Bengal; the Indus River basin running from the Punjab south to Sind; the Deccan upland plateau; and the peninsular south with both highlands and coastal plains. Their climates ranged from deserts to fertile plains to dense jungles.

Each macro-region also contained ecological micro-regions: each district contained significantly different soil and water conditions. Each macro-region also had particular patterns of rainfall and riverine irrigation, and thus a specific mix of wet and dry agriculture, with profound socio-cultural, economic and political consequences. Nonetheless, some broad characteristics occurred everywhere though with variations.

At the arrivals of the Mughals the Muslims were a combination of immigrants and their descendants but some were local converts who accepted Islam mostly under the influence of Sufis practicing eclectic creed of Islam that suited the prevalent multiplicity of religious beliefs amongst Hindus that were particularly fantasy-driven. Often, these Sufis had heterodox Islamic concepts and customs that incorporated many of the converting community’s pre-Islamic beliefs and practices especially domestic customs about birth, marriage and other rituals and women’s roles.

The largest concentrations of Muslims lived in the widely separated regions of India’s north-west and eastern Bengal. They had the advantage of being the ruling community though their governance control was very tenuous and was contested consistently.

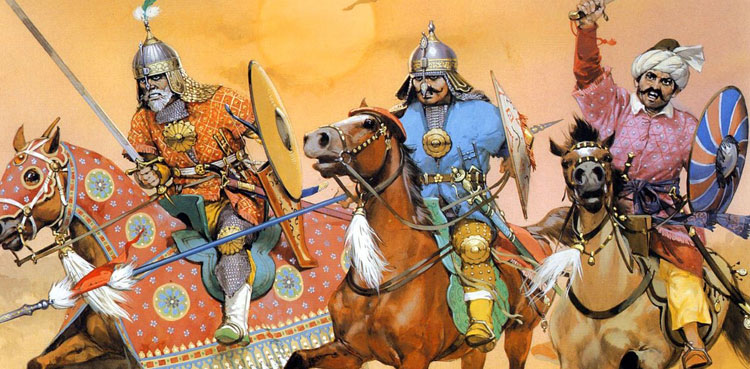

Since the early thirteenth century, Muslim Afghan immigrants had established themselves as landholders and rulers across the Gangetic plain and gradually they gained in power and influence. With the decline of the ruling Turks, the Afghans gained the strength to gain power resulting in the rule of Lodhi Afghans. When the Mughals arrived, a Lodhi Afghan sultan ruled in Delhi while other Muslim dynasties ruled in the Deccan. Although the Mughals would project themselves as the model Muslim rulers during some campaigns in north India, many Indo-Afghan Muslims regarded them as alien and fought against them. The first Mughal ruler Babur’s descendants would each negotiate the extent and expression of their roles as Islamic sovereigns.

Linguistically, South Asia also contains great diversity, with three major language families, dozens of separate regionally based languages and thousands of distinct dialects. Most north Indians speak one of the dozen languages derived from Sanskrit. Additionally, especially in the Deccan and the north-east, many forest-dwelling groups have their own languages unconnected to either Sanskrit or a Dravidian language. From well before Babur’s invasion, Persian had begun to dominate at Muslim courts, especially in the Deccan sultanates that had cultural, diplomatic and economic links across the Indian Ocean with Iran.

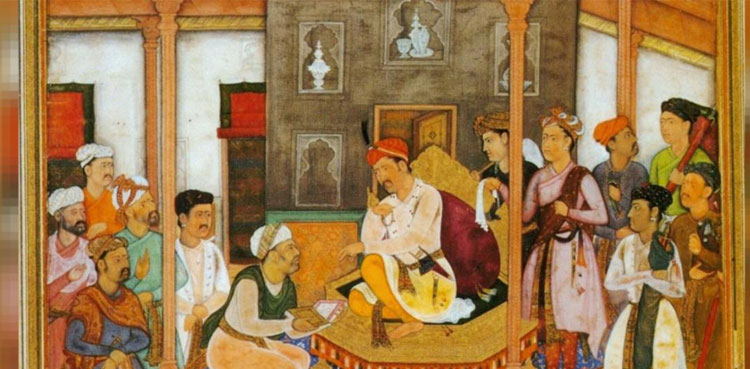

Gradually, the Mughal dynasty would shift from the Turki, Babur’s mother-tongue to Persian and adopt many accompanying Iranian administrative and cultural practices. Then, as the Mughal Empire expanded, its imperial Persianate culture and administrative forms became fashionable for other rulers, including Rajputs. The subcontinent became the hub of Persianate culture and deeply inspired its inhabitants.

Throughout India’s history, including during the entire Mughal period, the vast majority of its people have lived in an agriculturally based economy. When Babur arrived, he found that settled farmers held customary occupancy rights to plant and harvest although not full property landownership. Other local people or institutions also held their own separate rights to that same land. Most prominently, one or more levels of zamindars held rights to collect the revenues, retain a portion, and convey the rest to the state’s agents. Many zamindars based their claims on having originally settled or conquered the region.

The amount of revenue retained by zamindars depended on whether the land was directly managed by them or not, as well as on their power relative to the cultivators and the state. Village headmen, servants, accountants and local religious institutions also often had customary rights to a share of the produce. All these rights could be inherited, exchanged, or sold, with varying degrees of documentation required by various states.

At the arrivals of Mughals most regions of the subcontinent had much unused but potentially arable land. Hence, the land itself had limited economic value, although farmers often had invested in considerable labour to bring it under active cultivation. Control over people was more valuable than control over land. Thus, the revenue demands by zamindars or the state could not be so high as to drive farmers to emigrate and resettle new lands. Moneylenders and merchants made loans and purchased produce for sale in regional markets. Overall, zamindars, peasants, moneylenders and imperial administrators engaged in multi-sided cooperation and subtle or open contestation over agricultural resources. Each had his own interests in maximising income while minimising the economic and cultural costs of defending those interests.

Babur, trying to establish his regime quickly, often officially recognised those landholders who would at least pay some tribute, letting them assess and collect revenues from the cultivators.

Like many other rulers of that age, the Mughal dynasty would favor settled agriculturalists as their main revenue base. But settled agriculture was not strongly separated from other ways of life. For example, at times of drought or excessive revenue demand, farmers sometimes resorted to the forests, while periods of rain could attract former forest-dwellers to settled agriculture.

Further, some individuals, families, or whole communities customarily migrated. During the harvest season, male and female agricultural laborers often followed the shifting wave of ripening crops intra- or inter-regionally. During the fallow season, many village men joined mobile armies or formed their own bands, seeking plunder.

The Mughal state would never fully control this vast seasonal military labour market. Further, itinerant artisans and entertainers provided services to villages. Women and men hand-manufactured cloth and other products for sale which they, or brokers, carried to nearby market towns that were centers of regional commerce, concentrated artisan manufacture, inter-regional trade and governance.

In addition to the interrelated agricultural, pastoralist and forest-based economies, extensive long-distance trade routes in high-value, low-volume goods connected the country by land with the famous trans-Asian Silk Road. In particular, the subcontinent imported horses, vital for cavalry but constantly needing replacement due to uncongenial equine conditions, while exporting slaves and valuable man-made and natural products.