A new 3D printer uses light to transform gooey liquids into complex solid objects in only a matter of minutes.

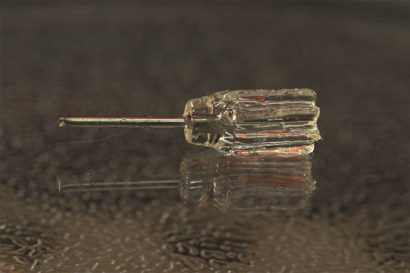

Nicknamed the “replicator” by the inventors — after the Star Trek device that can materialize any object on demand — the 3D printer can create objects that are smoother, more flexible and more complex than what is possible with traditional 3D printers. It can also encase an already existing object with new materials — for instance, adding a handle to a metal screwdriver shaft — which current printers struggle to do.

The technology has the potential to transform how products from prosthetics to eyeglass lenses are designed and manufactured, the researchers say.

“I think this is a route to being able to mass-customize objects even more, whether they are prosthetics or running shoes,” said Hayden Taylor, assistant professor of mechanical engineering at UC Berkeley and senior author of a paper describing the printer, which appeared in the journal Science.

Most 3D printers, including other light-based techniques, build up 3D objects layer by layer. This leads to a “stair-step” effect along the edges. They also have difficulties creating flexible objects because bendable materials could deform during the printing process, and supports are required to print objects of certain shapes, like arches.

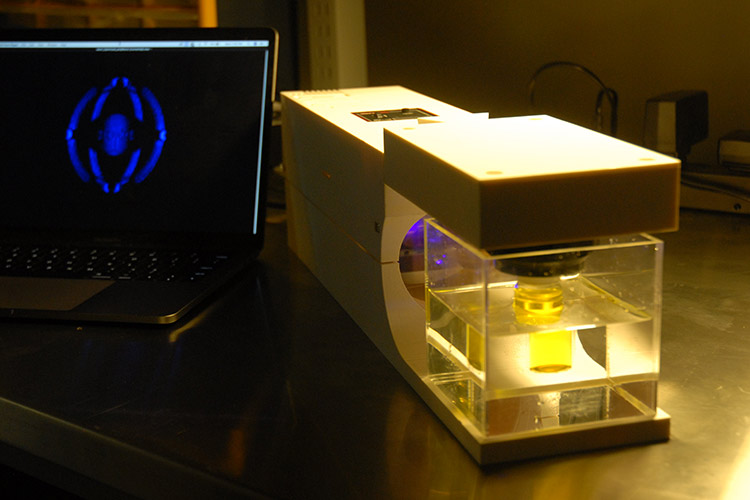

The new printer relies on a viscous liquid that reacts to form a solid when exposed to a certain threshold of light. Projecting carefully crafted patterns of light — essentially “movies” — onto a rotating cylinder of liquid solidifies the desired shape “all at once.”

“Basically, you’ve got an off-the-shelf video projector, which I literally brought in from home, and then you plug it into a laptop and use it to project a series of computed images, while a motor turns a cylinder that has a 3D printing resin in it,” Taylor said.

“Obviously there are a lot of subtleties to it — how you formulate the resin, and, above all, how you compute the images that are going to be projected, but the barrier to creating a very simple version of this tool is not that high.”

Taylor and the team used the printer to create a series of objects, from a tiny model of Rodin’s “The Thinker” statue to a customized jawbone model. Currently, they can make objects up to four inches in diameter.

The objects also don’t have to be transparent. The researchers printed objects that appear to be opaque using a dye that transmits light at the curing wavelength but absorbs most other wavelengths.

Indrasen Bhattacharya of University of California Berkeley is co-first author of the work. Other authors include Christopher M. Spadaccini of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

This work was supported by UC Berkeley faculty startup funds and by Laboratory-Directed Research and Development funds from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. The team has filed a patent application on the technique.